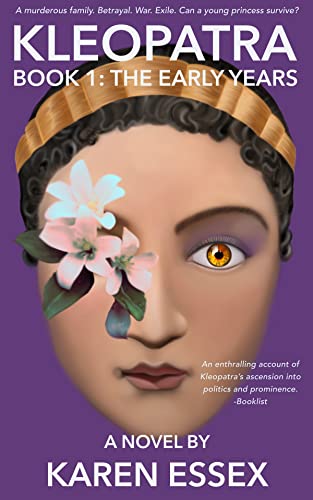

Karen Essex is the national and international bestselling author of five historical novels, including Leonardo’s Swans, Stealing Athena, Dracula in Love, and the two-volume biographical novel that reimagines Cleopatra, Egypt’s infamous queen: Kleopatra and Pharaoh. Earlier this year, Essex reclaimed worldwide rights to these two novels and decided to reissue them with striking new cover art. The new edition of Kleopatra released on September 15, with an October 1 release date for the new edition of Pharaoh.

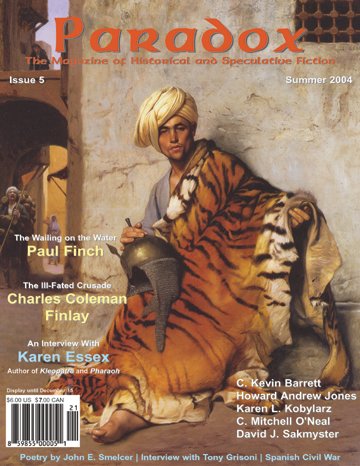

Back when I was publishing Paradox: The Magazine of Historical and Speculative Fiction, I interviewed Essex about her Kleopatra books shortly after they were first released. The interview appeared in issue 5 of the magazine (Summer 2004, pictured here), and I thought it might be fun to reprint that interview in the September 15 issue of my author newsletter to coincide with the books’ re-release. As a bonus, the text of the interview includes some new notes [in brackets] where Essex adds updates to her original answers. Enjoy!

What drew you to Kleopatra as the subject of your historical novels?

I was intrigued by the fact that the historical Kleopatra had little do with the Kleopatra brought to us by playwrights, popular culture, and Elizabeth Taylor. I wanted people to reexamine the very idea of Kleopatra, down to the spelling of her name. (I use the original Greek spelling because she was, as far as we know, Macedonian Greek, and that is how she would have spelled her name.) She’s been co-opted by every generation as an object and symbol of its own fantasies. I realize that in fictionalizing her once more, I have done a bit of that myself. But I want people to know that far from the sexual and treacherous archetype of feminine evil, Kleopatra was one of the ancient world’s most brilliant and powerful rulers.

She survived blood-curdling family rivalries for the throne, was queen by the age of eighteen, exiled by her brother by nineteen, and had regained her throne by twenty. She single-handedly ruled a rich nation with an eye for turning a profit, and kept Egypt independent while all its neighboring countries had been annexed to the Roman Empire. She spoke nine or ten languages, patronized art, drama, athletics, sciences and other forms of scholarship, and had the loyalty of her subjects—rare for the members of her dynasty. But like almost all women of power, she was reduced to her sexuality by historians and artists.

What sources did you find most valuable when researching Kleopatra’s life?

My bibliography is available on my website (karenessex.com), which might give you an idea of the breadth of the research. I researched for five years before I wrote a word. Then I continued the research through the writing of the two books and the screenplay [the book has been optioned many times, and in fact, is under option now but contractually, I can’t discuss it]. Everything was valuable. To give an idea of my process, I enrolled in an interdisciplinary graduate program at Vanderbilt University so that I would have access to all the right scholars, not to mention, a tremendous university library. For my tastes, anyone writing about history in any way can’t do without this latter resource.

After I did the academic research, I traveled to the actual locations so that I could breathe the air, which enabled me to breathe life and authenticity into the books. I traveled to Egypt, Greece, Turkey, and Rome, walking in Kleopatra’s footsteps. I studied not only Egyptian culture, but also Greek history, Roman history, and the history what is now the Middle East because Kleopatra’s story stretches over all those lands and cultures. I read what they were reading, studied the theater they saw, looked at their art, and studied the canon of what they were learning in the academy at the time.

Frankly, I got completely lost in the research for long periods of time, but I loved every minute of it. I am a perennial student. I cannot say that some of this research was more important than the rest of it. I threw it all into this incredibly large stew pot and then allowed it to come out dramatically in the novels.

Did you come to think of Kleopatra differently at the end of the research process than you did when starting out?

The character is still evolving in my mind, constantly informed by my own evolving point of view. I would say that the major realization I had about her as I researched was just how powerful and strong she was. Kleopatra was the only ruler of Rome’s “client kingdoms” that negotiated a partnership with Rome. The Romans simply did not do that. They didn’t negotiate. They came into a country, installed a Roman governor, and proceeded to collect huge taxes. Often, they allowed a country’s ruler to remain as a figurehead, but there was no Roman governor in Egypt while Kleopatra was alive. She was the only ruler able to negotiate with Rome, and to keep her country free. Roman propaganda written after she was dead would have it that she did all of this with her sexual charms. That is absolutely ridiculous. I think a huge treasury and a strategically located nation might have had a little more to do with her partnerships with both Caesar and Antony than that she was a vixen in bed.

To read the rest of the interview, subscribe to my newsletter!